.png)

Food security challenge divides Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

.png?width=56&name=Untitled%20design%20(3).png)

Economic news

The global food crisis has not bypassed the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). The region is arid and dependent on food imports, making it vulnerable to the disruption of global supply chains and the rise in global food prices. However, not all MENA countries have to be equally concerned about empty bellies or empty wallets. Energy exporters like the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members are clearly benefiting from the surge in oil and gas revenues. Their economies are booming, while food supplies are relatively secure through exclusive trade agreements and large-scale investments in overseas farmland. By contrast, countries that are net importers of both food and energy products, including Tunisia, Jordan, Egypt, Morocco and Lebanon, are being hit hard.

No country for farmers

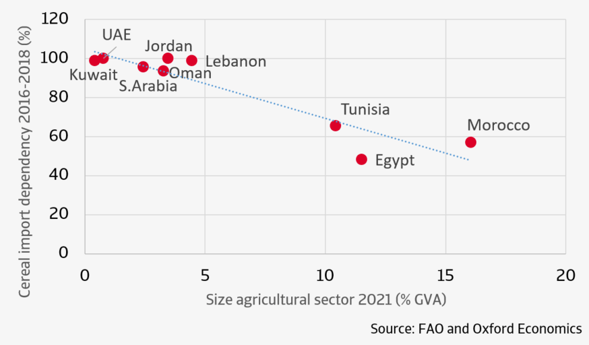

All MENA countries are highly dependent on imports for their food supply. Their gross import bills of food lie between 2% and 8% of GDP. The arid climate and lack of arable land limit homegrown agricultural production. The import dependency is especially evident for essential foodstuffs, such as wheat, which is largely imported. Gulf states are no exception here. Only Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia have a sizable agricultural sector, which generates more than 10% of the gross value added of their economies. And even there, about 50% or more of the grain supply is imported.

Figure 1: MENA’s cereal import dependency is high

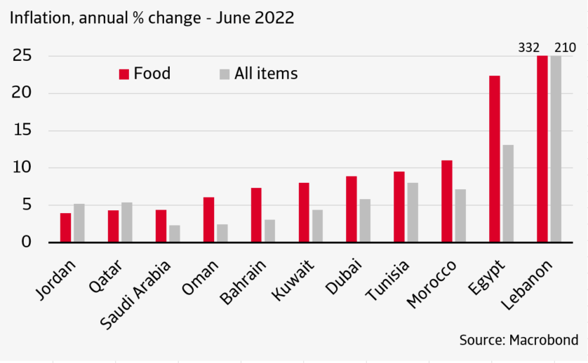

As a result, MENA is vulnerable to the 30% annual increase in the grain price on the world market in June, which is passed on to consumers. Aside from hyperinflation-ravaged Lebanon, the biggest inflation acceleration to date has been in Egypt, where consumer prices are rising by more than 13% year-on-year (figure 2).

Figure 2: Food scarcity drives up consumer prices

Gulf states have enough meat on the bones

The impact of higher food prices and disruptions of global food supply chains differs significantly across MENA countries. Wealthy GCC countries have a higher level of food security and are much better equipped to weather this shock.

First, consumers in the oil-rich Gulf countries are much more financially able to absorb the loss of purchasing power due to higher food inflation than elsewhere in the region. For example, per capita income, measured in purchasing power parity terms, is almost six times higher in Saudi Arabia than in Morocco. Second, the GCC economies are growing rapidly. This is due to the sharp rise in prices and demand for fossil fuels, as Russian oil and gas exports are increasingly shunned internationally. Real GDP in the GCC is expected to grow by an average of 5.6% in 2022, while economic growth in MENA’s net importing countries is projected to slow to 1.3%. Third, most Gulf states are less dependent on conflict countries Russia and Ukraine for the import of cereals. Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman and Saudi Arabia get less than 4% of their wheat directly from those countries, compared to around 25% for Morocco and Jordan and between 50-75% for Tunisia, Lebanon and Egypt. Finally, while Qatar and the UAE are the only two GCC countries that sourced a significant portion of their grain provision from Russia and Ukraine, they have easy access to additional food supplies from alternative trading partners, as they own stakes in their agricultural sectors. To increase food self-sufficiency, they have acquired farmland around the world, including in India – the world’s second-largest wheat producer – making the UAE and Qatar less affected by India’s wheat export ban.

MENA importers under pressure

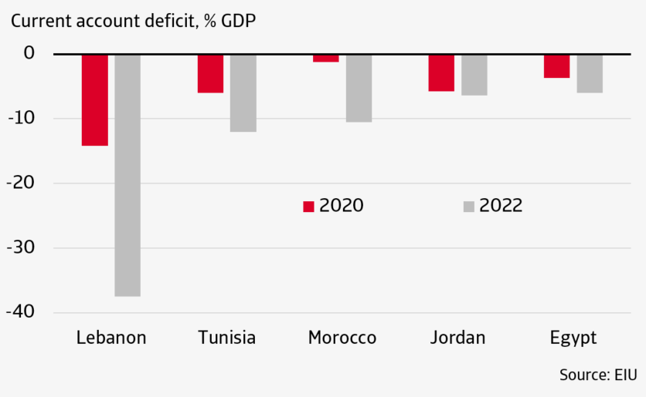

While the economic slowdown and rise in inflation are expected to be temporary, from a credit risk perspective, it is worrying that MENA countries such as Egypt and Tunisia are struggling with yet another deterioration in their macroeconomic imbalances. The rising import bill due to higher food and energy prices is already overshadowing the corona crisis recovery in export and tourism receipts. Current account deficits will therefore be even higher than during the peak in 2020 (figure 3). At the same time, government spending on economic support remains elevated on the back of higher food and energy subsidies.

Figure 3: Current account deficits exceed corona peaks

Figure 3: Current account deficits exceed corona peaks

Current account deficits exceed corona peaks

The financial space to absorb this new shock is clearly limited. All of MENA’s net importing countries have public debt ratios well above the IMF’s critical threshold for emerging markets of 70% of GDP. In addition, global interest rates are now rising, making external debt financing more expensive. For Lebanon, it means a deepening of its combined sovereign debt, balance-of-payments and humanitarian crisis it has been in since 2019. Tunisia and Egypt are potentially next in line to face financial trouble as they are running out of foreign exchange reserves and are seeking new IMF programs. Jordan and Morocco are the most shock-resistant among net importers with adequate foreign exchange reserves and decent access to both the international capital market and official loans.

We expect the GCC countries to use some of their petrodollars – which are currently flowing freely – to help their financially constrained neighbours. Such financial support has recently been given to Egypt and more or less pledged to Tunisia. GCC countries often act as lenders of last resort to prevent political instability in the region. However, to make MENA’s net commodity importing countries resilient to future shocks, financial aid has to be accompanied by far-reaching economic reforms and initiatives to improve food security and climate change preparation.

.png?width=66&name=Untitled%20design%20(3).png)