Energy transition not a panacea for fuel importers

.png?width=56&name=Untitled%20design%20(3).png)

Economic news

Countries around the world have seen their energy import bills rise sharply in 2022 due to the increase in energy prices. This has contributed to a deterioration of the balance of payments for those emerging market economies that are relatively dependent on foreign energy supplies. In the past decade, these countries have been subject to several episodes of energy price fluctuations on the world market. This vulnerability may decrease, however, as the recent energy crisis has accelerated the energy transition. We expect oil and gas prices, which are now normalising, to fall further over the next ten years.

Oil and gas prices are on a downward trend

We base this expectation on two scenarios from the International Energy Agency (IEA). We consider the most likely scenario to be the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS). This scenario assumes that governments will meet all current climate policy commitments already announced, however vague, in full and on time. The other scenario we have looked at is the Net Zero Emissions scenario (NZE), in which net CO2 emissions worldwide are reduced to zero in 2050. This scenario requires a tightening of climate policy. In both scenarios, the prices of oil and gas will decrease in the coming decades as policies to transition to the global energy mix effectively reduce demand for fossil fuels. Just how much the price will decline depends on the decisiveness of energy transition policies, dropping more sharply in the NZE scenario.

Energy importers are becoming more self-sufficient

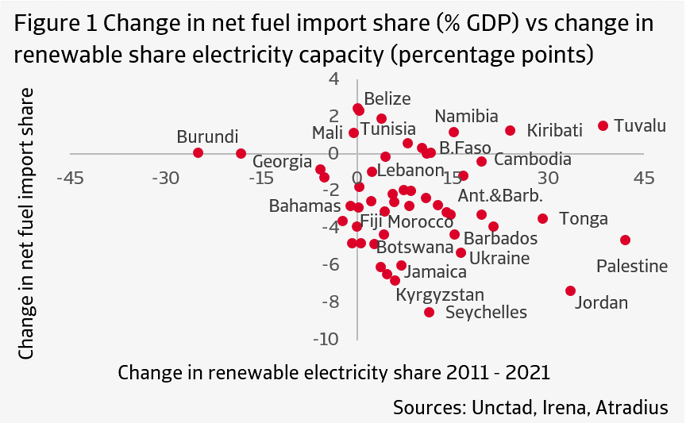

The energy transition also offers relief in terms of energy security. Imported fossil fuels will increasingly be replaced by domestically produced renewable energy. This process towards self-sufficiency is already underway: the fossil fuel import bill has been reduced on average from 8.4% of GDP in 2015 to 6.2% in 2021 among the 50 most energy-dependent emerging markets. The scatter plot (figure 1) shows that this decrease in fossil fuel imports was generally accompanied by an increase in the share of renewable energy in total power generation capacity. Over the past 10 years, this share has increased by about 10 percentage points and is now around 40%. In both the APS and the NZE scenario, an acceleration of the development of renewable energy sources is expected over the next ten years. This is particularly the case for countries with ambitious objectives and a solid policy framework, such as Morocco and Jordan. For many other emerging economies, however, the lack of financial resources to invest in the development of renewable energy remains a major obstacle.

Renewable energy is not a panacea

While permanently lower oil and gas prices and the development of renewable energy will make current energy-importing countries more self-sufficient and shock-resistant, it will not completely solve their financial problems. For most of them, the current account deficit is due not only to imports of oil and gas, but also to imports of other commodities, including food. In addition, a weak export base can hinder the financing of imports. In combination with the large investment needs of emerging economies, this often results in structural current account and budget deficits, which persist even in times of low oil and gas prices.

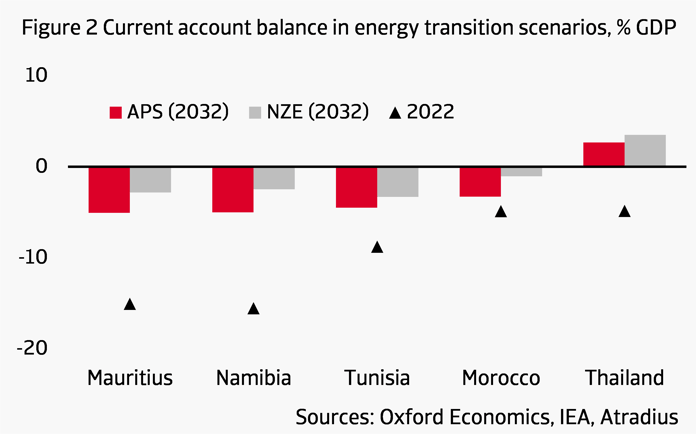

This persistence is confirmed by an analysis we conducted using the Global Economic Model of Oxford Economics. The oil and gas price paths of the APS and the NZE scenarios were imposed on this model. For the limited number of energy-importing emerging economies available in the model, current account deficits will narrow significantly during the energy transition, but in most cases, they will not be eliminated (figure 2). Positive exceptions are countries such as Thailand, which currently already have low current account deficits or even small surpluses, often due to compensating factors such as strong inflows of remittances from employees working abroad or a strong export base. The expected investment impulse in renewable energy is not fully included in the model and could initially also contribute to current account deficits, via higher import demand for capital goods, such as solar panels and wind turbines.

‘Net Zero’ is not zero risk

The energy transition does not solve the existing debt problems of many energy-importing emerging economies. As current accounts remain largely in deficit, this as such does not lead to a reduction in external debt. In fact, investments in renewable energy will largely have to be financed with new debt, because the countries concerned lack financial buffers. So while the energy transition can help reduce their country's risk by lowering the costs of energy imports and replacing imported fossil fuels with renewable energy sources, their macroeconomic imbalances, which are often deeply entrenched, will not easily disappear without broader economic reforms.

Read more in the full publication: Energy transition not a panacea for fuel importers

.png?width=66&name=Untitled%20design%20(3).png)